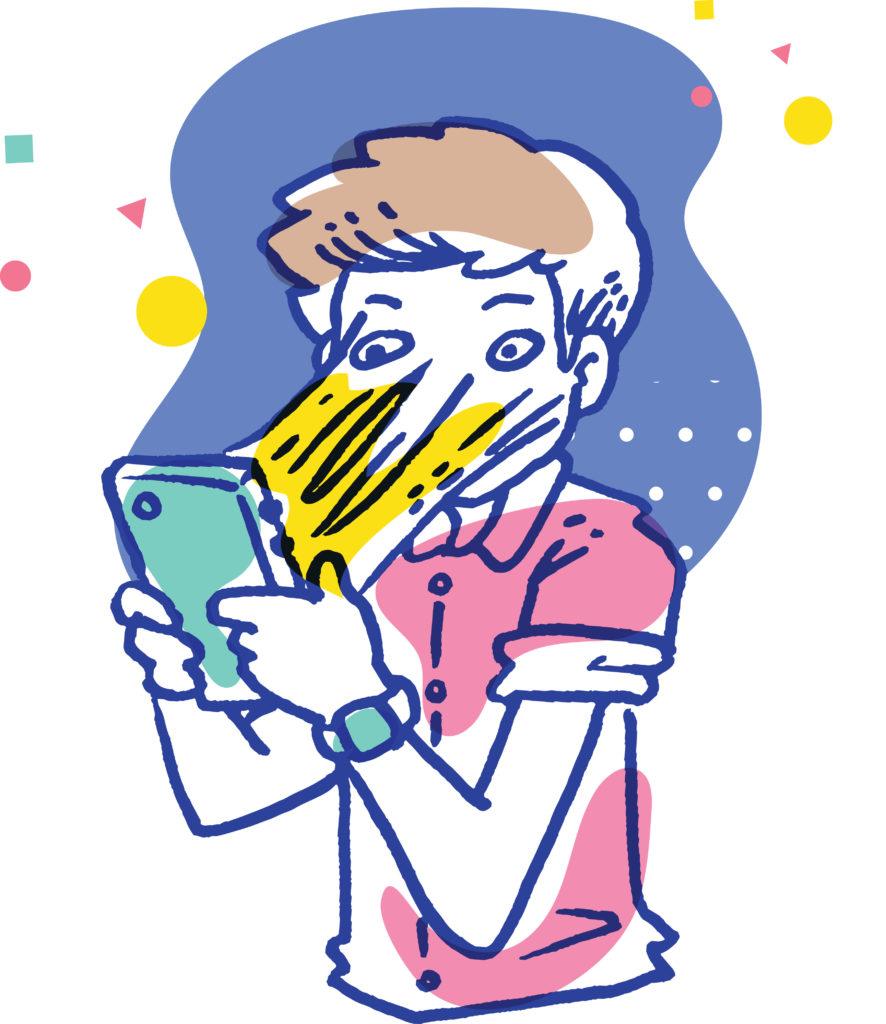

Device addiction

If you’ve read this column at all over the past six years, you’ll know that I’m not an alarmist. I tend to approach parenting (and pretty much everything else for that matter) with a healthy dose of skepticism. When I hear people start proclaiming the wonders of some parenting technique or the evils of some social trend, I mostly respond with caution. While these fads may have some value (there’s almost always a nugget of truth at the core of them somewhere), they rarely live up to their hype.

So, when I say that I think personal electronic devices are becoming the greatest threat to the mental health of children in North America, it’s not an ill-considered, band-wagon, alarmist position. I really believe it’s true, and that it’s becoming more true all the time.

Most parents, even those whose children are obviously addicted to their devices in unhealthy ways, respond with more or less polite scoffing when I say this. Most of them are too much invested in their own devices to see how their children are being affected. They’re too much reliant on the peace and quiet they can get by allowing their children to be distracted by the flicker of a phone or a video game screen. To admit that these devices are a social problem would mean both facing their own addictions and also having to engage with their children’s issues.

And yet, high device use, high social media use, and high video game use are all positively correlated (in many studies and in many ways) with anxiety, depression, bullying, low self esteem, and even suicide. Real psychologists now talk about social media addiction and video game addiction as actual conditions, and while only a small percentage of people can be classified as clinically addicted in this way, there is evidence that many people (especially young people) develop such a dependance on their devices that they show signs of withdrawal when forced to go without them.

And the impact on the lives of our children can be devastating.

One mother I know (who recently wrote a book about the experience) was called to come pick her son up from university. When she arrived, she found that he hadn’t attended a class in two months, had hardly eaten, washed, or left the apartment in all that time, and had done almost nothing but game compulsively. He had lost so much weight that he seemed anorexic. His clothes and his apartment smelled so bad she could hardly walk in the door.

Another family, friends of ours for almost 15 years now, finally had to remove their teenage son’s device because he was hardly sleeping or eating or even leaving his room. His emotional reaction during the withdrawal period was so intense that the police had to be called on more than one occasion. He screamed, smashed furniture, physically assaulted people, threatened suicide, and threatened the lives of his family.

A physiotherapist I know reports a growing number of people, especially young women, who are developing repetitive stress injuries because of how much they text. When she advises that they stop or at least greatly reduce the amount that they’re on their phones, the response if often literally tears – the fear of missing out on their social media is so strong.

Now, obviously not everyone is affected by their devices to this degree. But not everyone who drinks becomes an alcoholic either, and not everyone who gambles becomes an addict, yet we still recognize these things as sufficiently dangerous that we limit their availability to children and young adults. I think it’s time that we do the same with personal devices.

We need to recognize that young, developing minds are not always prepared to cope with the addicting, distracting, isolating qualities of personal devices, and we need to rigorously limit the amount that we expose children to these things. We need to talk with them about the ways that devices, social media, and video games can affect them. Most importantly, we need to model appropriate use of these devices ourselves as parents.

However much we might want to avoid it, this is a serious issue. We need to be taking it far more seriously than we do.